What is a Glycan Motif? 🧬

Imagine you’re looking at a complex glycan structure—those intricate branched molecules that decorate your cells. Hidden within these molecular architectures are recurring patterns called “motifs.” Think of them as the molecular equivalent of architectural motifs: recognizable design elements that appear across different buildings (or in this case, different glycans).

A glycan motif is simply a substructure that appears in multiple glycans. (Don’t confuse this with protein motifs—we’re talking about carbohydrates here! 🍭) Some famous examples include the N-glycan core, Lewis X antigen, and the Tn antigen.

Why Should You Care? 🤔

Here’s where it gets exciting: these motifs aren’t just decorative—they’re functional. They determine how cells interact, how pathogens bind, and how your immune system recognizes friend from foe.

This package, glymotif, is your computational microscope

🔬 for advanced glycan motif analysis. It helps you answer two

fundamental questions:

- Does this glycan contain a specific motif?

- How many times does this motif appear?

The best part? ✨ Everything works with vectors of glycans, so you can analyze hundreds or thousands at once.

Important note: This package builds on the powerful glyrepr package. If you haven’t used it before, we highly recommend checking out its introduction first.

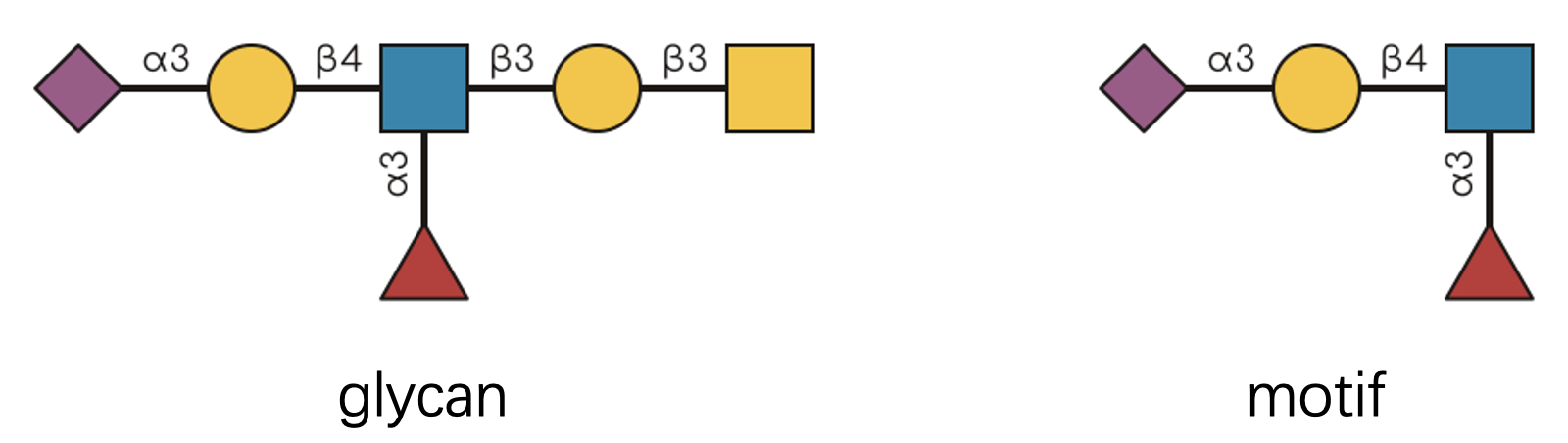

A Quick Challenge 🧩

Let’s start with a visual puzzle. Can you tell if the glycan on the left contains the motif on the right?

If you said “yes,” congratulations—you have a keen eye! 👀 But what

if I gave you 500 glycans and 20 motifs to check? That’s where

glymotif becomes indispensable.

Let’s see it in action using IUPAC-condensed notation (the standard

text format for glycans in the glycoverse ecosystem). If

this notation looks unfamiliar, don’t worry—check out this

helpful guide first.

glycans <- c(

"Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-3)[Fuc(a1-6)]GlcNAc(b1-3)Gal(b1-3)GalNAc(b1-",

"Neu5Ac(a2-?)Gal(b1-3)[Fuc(a1-6)]GlcNAc(b1-",

"Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-4)[Fuc(a1-3)]GlcNAc(b1-",

"Gal(b1-3)GalNAc(b1-",

"Neu5Ac9Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-"

)

motif <- "Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-3)[Fuc(a1-6)]GlcNAc(b1-"

have_motif(glycans, motif)

#> [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSEPretty neat, right? 😎

Your Toolkit: Four Essential Functions 🛠️

glymotif provides four core functions that work together

like a well-designed instrument panel:

-

have_motif(): Returns TRUE/FALSE for each glycan—does it contain the motif? -

count_motif(): Returns numbers—how many times does the motif appear? -

have_motifs(): The plural version—checks multiple motifs at once, returns a matrix -

count_motifs(): Counts multiple motifs simultaneously, returns a matrix

Why the Plural Functions? 🤷♀️

You might wonder: “Why not just use have_motif() in a

loop?” Great question! 💭 There are two compelling reasons:

1. Predictable output format 📊 Just like the

purrr package has different map functions for

different return types, our functions guarantee consistent outputs. The

singular functions return vectors; the plural functions return matrices.

No surprises, no wrestling with data types.

2. Optimized performance ⚡ The plural functions are

specifically optimized for multiple motifs. They’re significantly faster

than looping or using purrr::map() because they avoid

redundant computations.

Seeing Them in Action

Let’s define some motifs to work with:

motifs <- c(

"Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-3)[Fuc(a1-6)]GlcNAc(b1-",

"Fuc(a1-",

"Gal(b1-3)GalNAc(b1-"

)All functions follow the same pattern:

-

First argument: your glycans (as IUPAC strings or a

glyrepr::glycan_structure()object) -

Second argument: your motif(s) (IUPAC strings, a

glyrepr::glycan_structure()object, or predefined motif names)

have_motif(glycans, motif)

#> [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

unname(have_motifs(glycans, motifs)) # Removing names for cleaner display

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] TRUE TRUE TRUE

#> [2,] FALSE TRUE FALSE

#> [3,] FALSE TRUE FALSE

#> [4,] FALSE FALSE TRUE

#> [5,] FALSE FALSE FALSEPro tip: 💡 You don’t need to memorize complex IUPAC strings! Use predefined motif names instead:

db_motifs()[1:10]

#> [1] "Blood group H (type 2) - Lewis y" "i antigen"

#> [3] "LacdiNAc" "GT2"

#> [5] "Blood group B (type 1) - Lewis b" "LcGg4"

#> [7] "Sialosyl paragloboside" "Sialyl Lewis x"

#> [9] "A antigen (type 3)" "Type 1 LN2"

have_motif(glycans, "Type 2 LN2")

#> [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSECaution: If you are using predefined motif names, you should be aware that all of the built-in motifs have “intact” structure level. See the “Handling Structural Ambiguity” section below for more details.

The Art and Science of Motif Matching 🎨🔬

Now we enter the fascinating complexity of motif recognition. You might think: “It’s just pattern matching, right?” Well, not quite. 🤨

Real-world glycan data is beautifully messy:

- Missing linkage information: Sometimes we only know “there’s a link” but not its exact type

- Generic monosaccharides: Mass spectrometry might only tell us “Hex” instead of “Glucose”

- Chemical modifications: Sulfation, acetylation, and other decorations add complexity

- Alignment constraints: Some motifs only “count” when they appear in specific locations

Consider the Tn antigen—it’s just a single GalNAc residue. But it shouldn’t match every GalNAc in a complex N-glycan, should it? Context matters.

Similarly, an O-glycan core motif should only be recognized at the reducing end, not buried in the middle of a structure.

glymotif handles all these complexities through its

sophisticated matching engine. The algorithm considers structural

context, chemical modifications, and biological relevance to make

intelligent matching decisions.

Handling Structural Ambiguity 🤔

Real-world glycan data often comes with structural ambiguity. Mass spectrometry might only tell us “HexNAc” instead of “GlcNAc”, or linkage analysis might yield “a1-?” instead of “a1-6”. These uncertainties are common in experimental glycomics and glycoproteomics.

How glymotif Handles Structural Ambiguity

glymotif handles these ambiguities with a fundamental

principle: A glycan cannot be more ambiguous than the motif it’s

being matched against.

# Ambiguous linkages won't match specific ones

have_motif("Gal(??-?)GalNAc(??-", "Gal(a1-6)GalNAc(a1-")

#> [1] FALSE

# Generic monosaccharides won't match specific ones

have_motif("Hex(a1-6)HexNAc(a1-", "Gal(a1-6)GalNAc(a1-")

#> [1] FALSEThis behavior is intentional, not a bug. ✨ True motif identification requires confidence: structural possibilities alone aren’t sufficient evidence.

Working Around Ambiguity

If you’re getting unexpected FALSE results with

have_motif() (especially when using built-in motifs with

ambiguous glycans), the first thing you should do is to check the

structure level of the glycan and the motif. You can use

glyrepr::get_structure_level() to help you with this

task.

# get_structure_level() expects a glycan structure vector

get_structure_level(as_glycan_structure(c("Gal(??-?)GalNAc(??-", "Gal(a1-6)GalNAc(a1-")))

#> [1] "topological" "intact"here are two strategies:

1. Ignore linkage information when linkages are unreliable:

have_motif("Gal(??-?)GalNAc(??-", "Gal(a1-6)GalNAc(a1-", ignore_linkages = TRUE)

#> [1] TRUE2. Convert motifs to generic forms to match the generic monosaccharides of your data:

motif <- glyparse::auto_parse("Gal(a1-6)GalNAc(a1-") # First, create a `glycan_structure()`

motif <- glyrepr::convert_to_generic(motif) # Then, convert to generic

have_motif("Hex(a1-6)HexNAc(a1-", motif)

#> [1] TRUE⚠️ Important: When using these workarounds, interpret your results with appropriate caution. You’re trading specificity for coverage.

Dynamic Motif Detection

While matching against a database of known motifs is powerful, sometimes you want to discover what motifs are actually present in your specific dataset, even those not in the database. This is where dynamic motif detection comes in.

Instead of asking “Is motif A here?”, we ask “What motifs are here?”.

extract_motif()

extract_motif() allows you to detect all motifs appears

in a set of glycans. Take a simple O-glycan for example:

extract_motif("Gal(b1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-6)]GalNAc(a1-")

#> <glycan_structure[6]>

#> [1] Gal(b1-

#> [2] GlcNAc(b1-

#> [3] GalNAc(a1-

#> [4] Gal(b1-3)GalNAc(a1-

#> [5] GlcNAc(b1-6)GalNAc(a1-

#> [6] Gal(b1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-6)]GalNAc(a1-

#> # Unique structures: 6This function works vectorizedly, and only a unique set of motifs will be returned.

extract_motif(c(

"Gal(b1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-6)]GalNAc(a1-",

"Gal(b1-3)GalNAc(a1-"

))

#> <glycan_structure[6]>

#> [1] Gal(b1-

#> [2] GlcNAc(b1-

#> [3] GalNAc(a1-

#> [4] Gal(b1-3)GalNAc(a1-

#> [5] GlcNAc(b1-6)GalNAc(a1-

#> [6] Gal(b1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-6)]GalNAc(a1-

#> # Unique structures: 6As you can imagine, the number of possible dynamic motifs in a large

glycan can be very large. Therefore, extract_motif() has a

max_size parameter restricting the size of motifs to be

extracted. By default, max_size = 3, this restricts the

motifs to be extracted to those with at most 3 monosaccharides.

extract_motif("Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-")

#> <glycan_structure[3]>

#> [1] Glc(a1-

#> [2] Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-

#> [3] Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-

#> # Unique structures: 3You can increase the max_size to extract larger

motifs.

extract_motif("Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-", max_size = 4)

#> <glycan_structure[4]>

#> [1] Glc(a1-

#> [2] Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-

#> [3] Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-

#> [4] Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-2)Glc(a1-

#> # Unique structures: 4However, increase it progressively with caution, as the computation time can increase exponentially.

extract_branch_motif()

extract_motif() works well with O-glycans, which are

very versatile and not very large. However, using it on N-glycans might

be less effective and less meaningful, as the core pattern of an

N-glycan is very restricted by the biosynthesis rules. The only

diversity comes from the antennae. Therefore, we provide

extract_branch_motif() to extract only the branching

motifs.

glycans <- c(

"Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1-",

"Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1-",

"Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1-"

)

extract_branch_motif(glycans)

#> <glycan_structure[4]>

#> [1] Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-

#> [2] Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-

#> [3] Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-

#> [4] GlcNAc(b1-

#> # Unique structures: 4

dynamic_motifs() and branch_motifs()

extract_motif() and extract_branch_motif()

are useful if you only want to know what motifs exist. However, when

using dynamic motifs in motif matching functions like

have_motifs(), additional intricacies should be taken into

account.

For these cases, you should pass the dynamic_motifs() or

the branch_motifs() helpers to the motifs

argument of supported functions instead. They are just empty sentinel

objects to inform the passed functions to perform dynamic motif

matching.

count_motifs(glycans, branch_motifs())

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 1

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 1

#> Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 0

#> Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 1

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 0

#> Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 1

#> Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 0

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 1

#> Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 0

#> GlcNAc(b1-

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 0

#> Neu5Ac(a2-3)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[Neu5Ac(a2-6)Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 0

#> Gal(b1-4)GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-3)[GlcNAc(b1-2)Man(a1-6)]Man(b1-4)GlcNAc(a1-4)GlcNAc(b1- 1Functions supporting dynamic_motifs() and

branch_motifs(): have_motifs(),

count_motifs(), match_motifs(),

add_motifs_lgl(), and add_motifs_int().

What’s Next?

- Want to known all the details about motif matching rules? Here

- Working with

glyexp::experiment()? Here

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants 🏔️

This work wouldn’t be possible without the inspiration and groundwork laid by several excellent projects:

- glycowork: A comprehensive Python toolkit for glycan analysis 🐍

- GlyCompare: Advanced glycan comparison algorithms 🔬

We’re proud to contribute to this growing ecosystem of computational glycobiology tools! 🌱